Get Single Tutorial

Learn Enough Ruby to Be Dangerous is available as an ebook, an offline video series, and as a structured, self-paced online course. The course includes full online access to the book content, streaming videos, progress tracking, exercises, and community exercise answers.

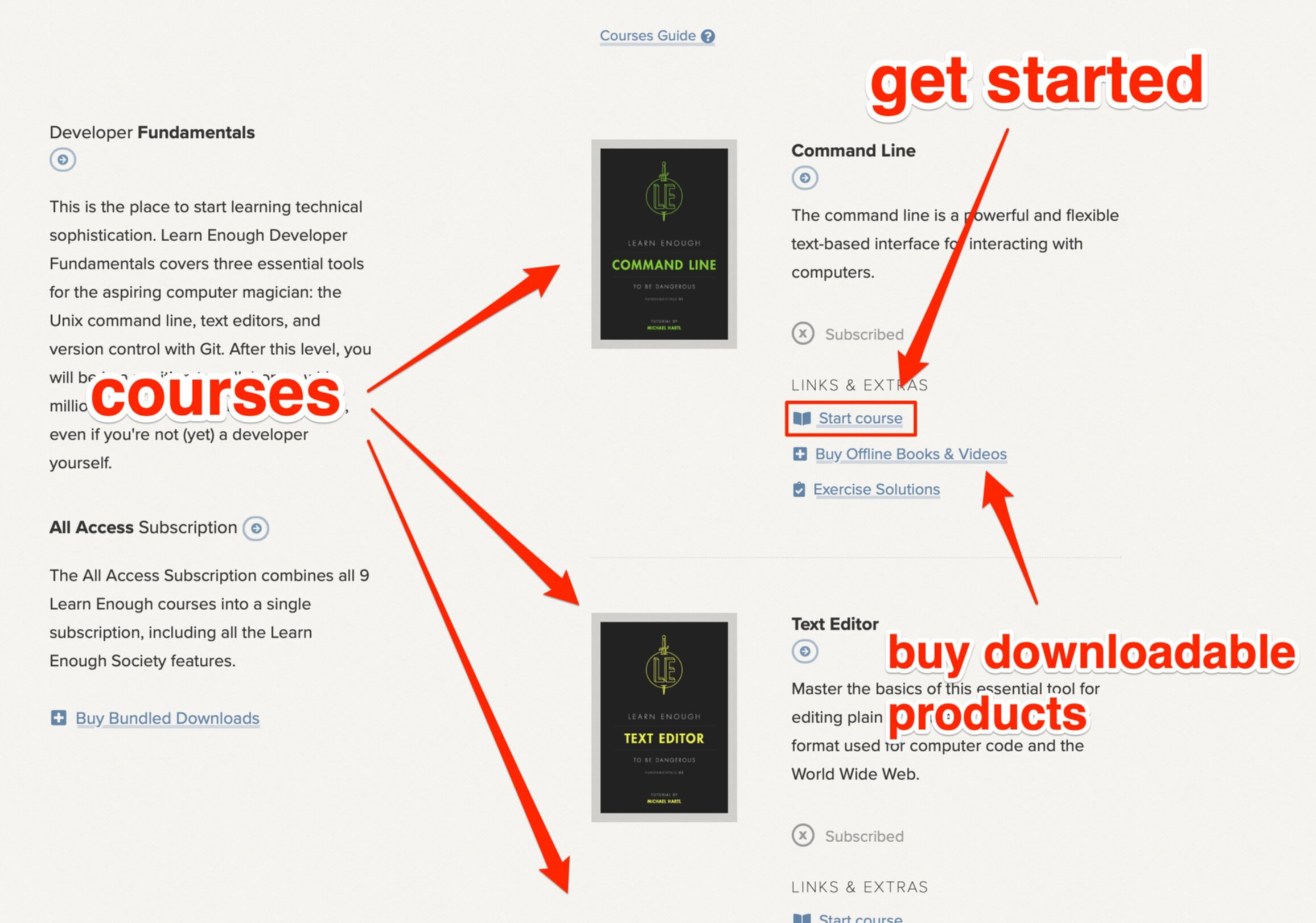

All Access Subscription

The Learn Enough All Access Subscription includes the entire Learn Enough introductory sequence and the full Ruby on Rails Tutorial. More than 2500 pages of book content and 53 hours of video that teach you to code from total beginner up to professional-grade web development.

All Access Subscription

Get free access to all 10 Learn Enough courses (including the Ruby on Rails Tutorial) for 7 days!

Free 7 Day trial details

We require a credit card for security purposes, but it will not be charged during the trial period. After 7 days, you will be enrolled automatically in the monthly All Access subscription.

BUT you can cancel any time and still get the rest of the 7 days for free!

All Learn Enough tutorials come with a 60-day 100% money-back guarantee.